LANGUAGE REVITALIZATION

The most impactful take home moment for me in Young’s piece ‘Anishinabemowin: A way of seeing the world: Reclaiming my identity,’ was their firm reminder that maintaining language is vital to maintaining the spirituality of a community, and in turn its spirituality is vital to community health. I loved the idea that Indigenous languages should be spoken in class without being in service to english education, free from reductionist translations and drawing unnecessary parallels. Allowing the worldview and stories embedded in language to be stand alone. It was so clearly shown in the following quotation:

I asked my sister to pass the salt and pepper in English, and without looking at me my father said, “Intanishinabemowin nun awind oma biiting.” We speak Saulteaux in this house. He did it without chastising or embarrassing me; he simply wanted to remind me that the language spoken in our home was Saulteaux. (Young).

This shows the deep respect that is shared across generational divides because ultimately it is through relationship building that long-term preservation is ensured, especially when it comes to cultural practices. This includes the cultural practice of using one’s first language. Many classes ago, a peer mentioned that when you travel to any other country in the world, it is common courtesy to learn at least a few common phrases to get you by- your pleases, your thank yous, your hellos. And how insulting and telling it is that we don’t learn the phrases of the land we are visiting when it is occupied Indigenous territory. When we are in fairway market, and the cashier flashes one last smile before we walk out the door, why are we not saying HÍSW̱ḴE, the smallest acknowledgement of your respect for being in someone else’s home And ultimately I believe it’s because it plays into colonists’ fears of being displaced, ironically the very thing that my ancestors have systemically and routinely attempted to do to Lekwungen, WSANEC and Coast Salish groups for hundreds of years on the island.

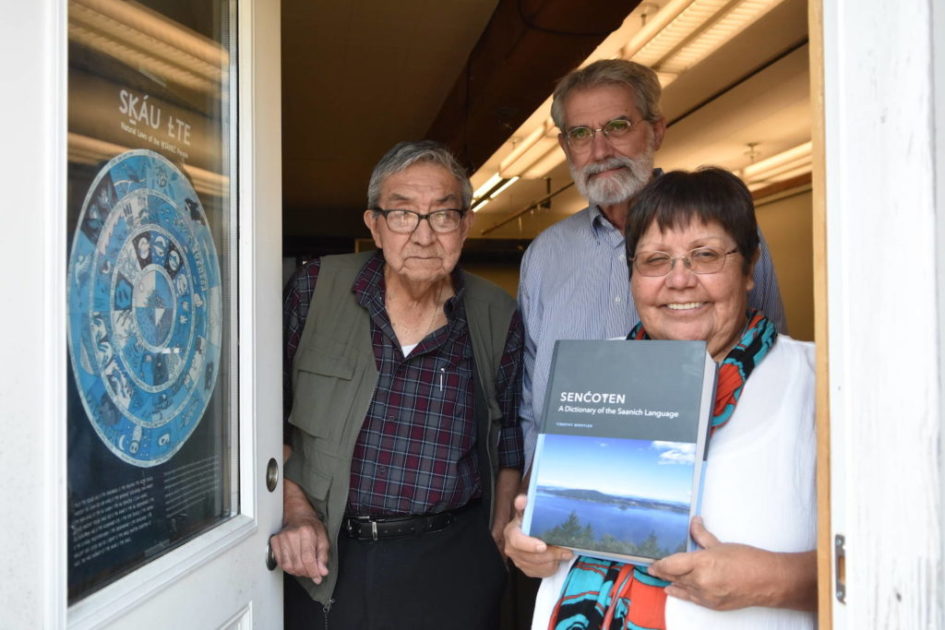

Given that we are moving into the role of teaching a new generation of Coast Salish, Indigenous, settler, newcomer and refugees alike, it is a professional responsibility to learn more SENĆOŦEN and to try and normalize it into lessons and speech. By introducing to students early exactly what territory they are visiting (for those settlers who need to know, Coast Salish kids are well aware they are on the salish sea) then I believe teachers can normalize discussions around sovereignty and getting land back to its rightful caretakers and begin to help students sit in discomfort without being immobilized by it.

My question: How to teach spiritual privacy to curious young people who want access to all the information when they have not culturally inherited the right to access certain pieces of knowledge?

Leave a Reply